Value Based Decision Making (VBDMSM)

by Andrew Boyes-Varley

Millions of decisions are taken in businesses every day, ranging from trivial to transformational; some generating value and some destroying it. For example, of 170 global merger and acquisition transactions worth at least $75 million over the period January 2007 to mid-2009 a third destroyed value and a third had no effect on share prices*. Value generation in business requires focussed actions resulting from wise decisions.

Most businesses today have allocated decision accountabilities to improve the efficacy of material decisions. There are a number of frameworks that can be applied to this aspect of the decision-making process; two examples are RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) and RAPID ® (Recommend, Agree, Perform, Input, Decide). While the ‘who’ in the decision process is addressed by these frameworks, not many businesses have codified the ‘what’ in terms of a formal or even informal cognisance of the three critical elements of value generation. These are: (i) the experience the customer is willing to pay for – which creates value; (ii) the costs the business is to incur to deliver value – i.e. the surrender of a portion of the value; and (iii) the risks that could potentially destroy some or all of the value.

Decision-makers likely consider these elements instinctively in their decision-making process and for less-material decisions this level of consideration should suffice, as long as all three elements are taken into account. However, for the more-material decisions that a business faces a framework with more rigour than business instinct is appropriate. Value Based Decision Making (VBDMSM) is one such framework and is set out below.

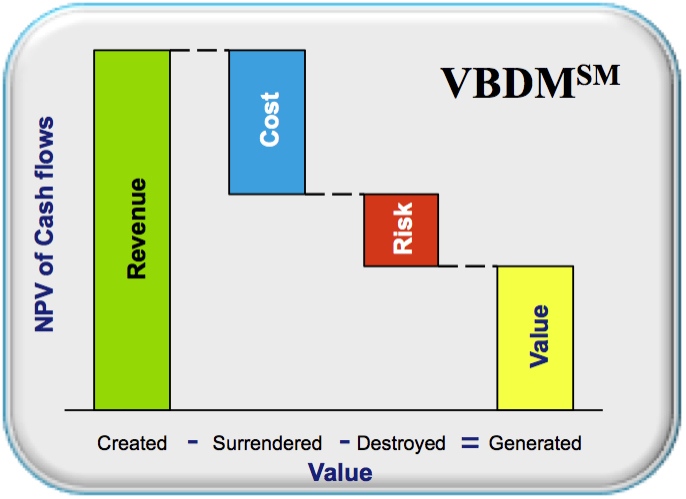

While numerous methods and frameworks exist to assess each of the three value-generating elements individually, the crux of Value Based Decision Making (VBDMSM) is to factor in all three elements together in the decision process to generate maximum value: customer experience – maximise value creation; cost – minimise value surrender; and risk – constrict value destruction. These elements are interrelated and a tension exists between them, which means that should actions be taken that raise or lower one element there is likely to be a corresponding effect on the other two (see figure 1).

Figure 1: The three value-generation elements: ‘value created’, ‘value surrendered’ and ‘value destroyed’ interrelate to generate value.

VBDMSM can be expressed in formulaic terms, whereby: value generation (Vg) is a function of the value created (Vc), the value surrendered (Vs) and the value destroyed (Vd).

Vg = f(Vc, Vs, Vd)

The crucial point of VBDMSM is to bring all three elements into the decision equation. As the focus is on value, expressed in monetary terms, the framework leverages the established norms of discounted cash flow to consolidate the value impact of each of the three elements. Value created is expressed as the present value (PV) of future cash in-flows as a result of the decision. Value surrendered is expressed as the PV of future cash out-flows as a result of the decision. It is common practice to set-off these two streams of discounted cash flows against each other to provide an expected net present value (NPV) of the actions to be taken as a result of the decision. Unfortunately, this is often where rigorous analysis stops.

A qualitative view of the risks surrounding the decision may be considered, but the third critical element of value generation – risk and its potential for value destruction – is seldom quantitatively included in the decision process. It is relatively straightforward to include risk and its associated value destruction element in the NPV framework. Including the PV of potential value destruction, the value generation equation can be restated as in the equation below.

Vg = (PV Vc) – (PV Vs) -(PV Vd)

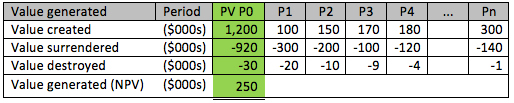

The potential value destruction arising from a decision needs to be estimated in cash flow terms by period, and the PV determined for inclusion in the overall NPV calculation (see table 1) for a simple example of the NPV calculation. The critical question then becomes one of establishing the appropriate cash flow amounts for each of the three value elements.

Table 1: Simple example of NPV table illustrating the consolidation of the three value generation elements

of value created, value surrendered and value destroyed

Value creation – Quality of the Customer Experience (QOCE)

At the apex of value creation for businesses is the revenue that they earn from their customers. Growing this revenue will require taking action to retain customers, to acquire new customers and to grow both new and existing customers’ business. This imperative for action means that value-generating decisions need to be made.

The revenue earned is as a result of customers being willing to pay a price for the products and/or services supplied based on the quality of the product and/or service which is perceived by the customer in terms of their ‘customer experience’ (see sidebar). The better the quality of the customer experience (QOCE), the more revenue a business will be able to sustainably earn. The delivery of the QOCE will incur a COST and there will likely be a positive correlation between these two elements. Similarly, the approach taken to rendering the QOCE will also have a relationship with the third value-generation element – RISK.

The determination of the cash in-flows associated with the delivery of the QOCE will be well understood and relatively straightforward for most businesses.

Value surrender – COST

Likewise, the cash out-flows, as represented by the cost element to be incurred in order to generate the revenue, will be a centrepiece of most of the analyses undertaken for material business decisions. These costs typically would include all of the aspects of one-off, ongoing, capitalised, operating, financing and taxation costs. The key area of focus is to ensure that all relevant future costs are included and sunk costs are excluded from the value-generation equation. The costs incurred will depend on the approach to the QOCE and tolerance for risk. For example, risk can be controlled, shared or even transferred for an additional cost.

Minimisation of cost, with no change in value creation (revenue) can also be accommodated in the VBDMSM framework. The cash flows to be included for value surrender in this circumstance would be the net cash in-flows for each of the periods impacted by the decision. The inflow being equal to the cost saving, net of any cost incurred to make the saving. A simple example to illustrate this point could be the reduction of staff who are surplus to the number required to support the ongoing revenue of a business unit. The by-period cash in-flows would be the dollar amount of the reduction of the staff cost, after taking into account any severance costs.

Value destruction – RISK

The potential cash flows that result from the value destruction element, RISK, are not commonly quantified. This paper now begins to examine the key aspects of this element and set out a perspective on its quantification.

Risk is the threat of an event that will adversely affect the ability of the business to generate value. Risk has two elements: likelihood and consequence. Risk management entails the systematic identification, analysis, treatment and monitoring of risk. The VBDMSM framework suggests a five-step process to arrive at a quantification of the risk element.

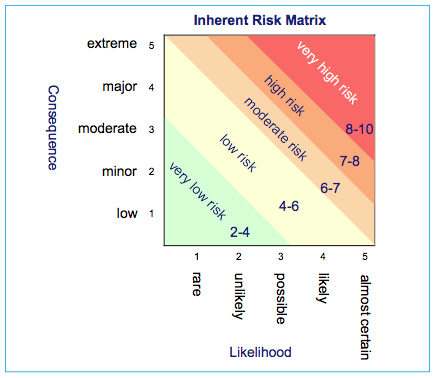

The first step in quantifying the risk element is to form a view on the likelihood or probability of the risk event occurring. This view formation may take into account aspects such as the complexity of the circumstances surrounding a decision, the susceptibility of the organisation to an adverse result from the decision or other historical factors relating to the decision that may affect the outcome. Experts or well-informed managers should be able to classify the likelihood along a scale such as almost certain, likely, possible, unlikely or rare, or to ascribe an actual probability value.

The second step is to form a view on the consequence of the event occurring. This view can be expressed on a scale ranging from insignificant to catastrophic. The aspects for consideration include: financial impact, client experience, staff experience, business continuity, regulatory, legal, reputation, image, environment, community and human life. Each of these aspects could be rated on a continuum from low, minor and moderate to major or even extreme.

Third, combining the results of the analysis of steps one and two will present a perspective on the inherent risk of the event. This is most clearly depicted by way of the Inherent Risk Matrix in figure 2.

Emotion and the customer experience

On a simple three-point scale, customers are delighted, satisfied or disappointed with the customer experience they receive. These are all emotional states and it is in the emotional realm that customers experience a product and/or service quality for the price they agreed to pay.

The customer’s assessment of the quality of their experience is based on expectations that are inextricably linked to the price. A higher price equals higher expectations.

The emotional state that arises as a result of the customer’s experience is determined by comparing the perception of the experience to the expectations formed (largely based on price, but also brand, reputation, design and a host of other potential factors).

What attributes do customers consider? These fall into two categories; let’s call them ‘hygiene attributes’ and ‘motivating attributes’ (borrowing from Frederick Herzberg’s two factor theory).

Hygiene attributes are typically characterised by use or usability aspects, such as : availability, reliability, accuracy, courtesy, cleanliness, consistency, trustworthiness and timeliness.

Motivational attributes are characterised by meaning or purpose. Examples of these include: responsiveness, confidence-inspiring interaction, unexpected ‘add-on’ features and empathy.

Surpassing customers’ expectations in relation to motivational attributes will likely give rise to a delighted response, while surpassing expectations related to hygiene attributes will be unlikely to elicit more than a satisfied response.

Failing to meet customers’ expectations on both hygiene and motivating attributes will likely lead to disappointed customers, as can failing on either.

In summary, the potential to delight customers only exists via surpassing expectations related to meaning while at least meeting those regarding use and usability.

Figure 2: The inherent risk matrix, which combines consequence and likelihood to give an inherent risk rating.

The fourth step is to decide on the treatment the business is to apply to the inherent risk. Four options exist:

- Reduce: through the deployment of controls (policies, procedures, processes and practices), the business may be able to reduce either of or both the likelihood and consequences of the occurrence of the risk event

- Share or transfer: it may be possible to reduce the impact of the inherent risk through a sharing arrangement or complete transfer of the risk to another party

- Avoid: decide that the residual risk after all possible treatments (controls, share or transfer) is unacceptable and do not proceed with the risky actions

- Accept: either the inherent risk untreated or the residual risk after treatment (controls, share or transfer).

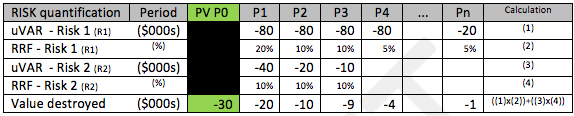

The fifth step is the quantification of the monetary exposure of the residual risk that is to be accepted by the business, in the light of the above analysis. The untreated value at risk (uVAR) – the accepted risk – is to be established as the possible cash out-flows by cash flow period should the risk event occur. An example of this could be the uninsured portion of a risk event that was treated by means of an insurance policy. The residual risk factor (RRF) also needs to be established and should be expressed in percentage terms. The RRF is the probability that the uVAR will materialise during a particular cash flow period. The equation for the value destroyed for a cash flow period (P1) can be expressed as:

VdP1 = (uVAR R1P1 x RRF R1P1)+ (uVAR R2P1 x RRF R2P1)+ … + (uVAR RnP1 x RRF RnP1)*

* R1 is the first risk and Rn is the nth risk considered in period 1

Should a risk event have the potential to occur in more than one cash flow period the uVAR should be established for each period and the associated RRF should be calculated for each period, but if the event could only occur once in the life of the cash flows then the RRF should be apportioned over the relevant cash flow periods, with the sum of all of the RRFs for the event to total to the probability that the event will occur. The distribution of the RRF over the cash flow periods may not be even, as the probability of the risk occurring could increase or decrease over time (see table 2).

Table 2: Simple example of the risk-quantification calculation

It is recognised that the actual value destroyed in any period will not equate to the estimated value destroyed as the risk event either will or will not occur, which means that the actual value destroyed in relation to a particular risk will either be zero (if it did not occur) or it will be the uVAR for the period (if it did occur). Notwithstanding this technical imprecision, the benefit of factoring in the estimated value destroyed in the value-generation equation will enhance the calibre of the decision, as the risk element will have been appropriately considered and included in the decision process.

In summary then, Value Based Decision Making (VBDMSM) is a framework designed to maximise the value generation of business decisions by highlighting the need to take account of the three critical value elements: the experience the customer is willing to pay for – the creation of value; the costs the business incurs to deliver the value – the surrender of a portion of the value; and the risks which could destroy the value created. These elements are interrelated and need to be assessed as such. VBDMSM is applicable to all business decisions where value is important , whether in a formal rigorous approach – such as in building models to represent the detailed cash flows associated with each element – or even when analysis is undertaken on the proverbial ‘back of the envelope’.